The men in all the photographs looked rugged and weather-beaten. Sophie Elmhirst kept looking at the faces, one after the next. She was researching an article about all the ways people were responding to the pandemic, including by trying to escape in boats headed offshore.

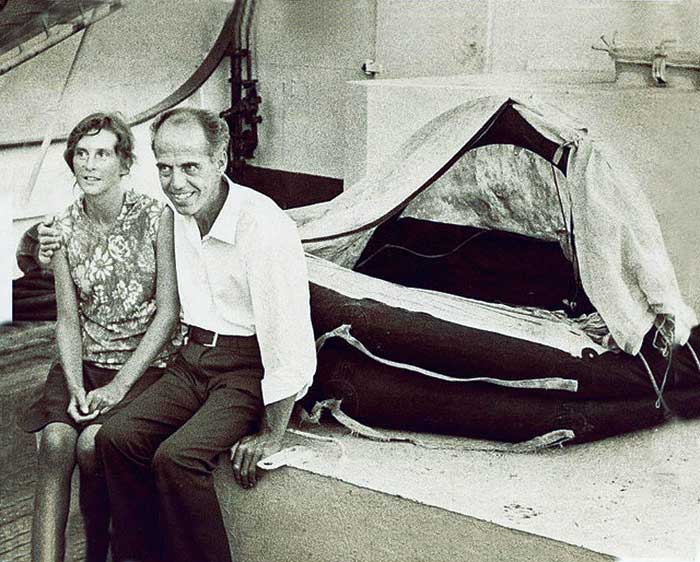

Then her research brought her to a series of photos of boat-sinking survivors and the images made it clear that freedom from life on land didn’t necessarily turn out to be all sunshine and blue skies. Two particular faces captured Elmhirst’s attention.

“There was a picture of Maurice and Maralyn Bailey, who I’d never heard of before,” she says. “The more I dug into it, and once I started finding all the source material and people who were still alive that knew their family and friends, it felt like a story that deserved retelling.”

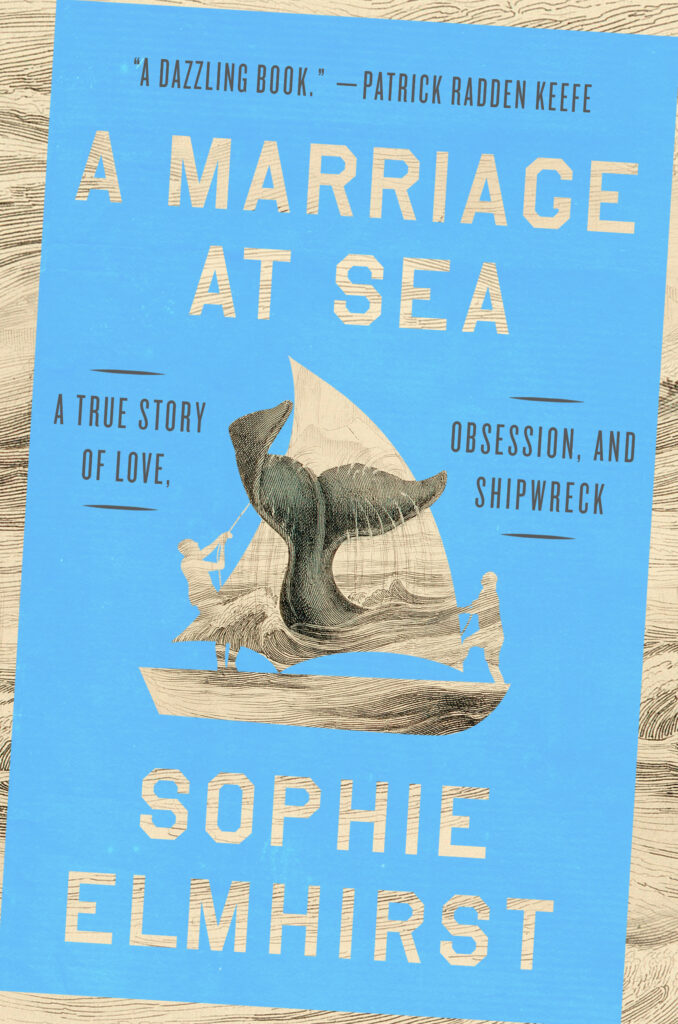

Elmhirst’s new book, A Marriage at Sea, investigates not only what happened to the couple after a whale struck and sank their 31-foot Bermuda sloop Auralyn in the 1970s, but also what happened between the two of them out there alone. As it turns out, the experience helped to shape their marriage for the rest of their lives.

The Baileys wrote their own book, 117 Days Adrift, back in 1974, but it’s mostly factual, Elmhirst says. It ends with their rescue and omits the psychology of what they endured—something people didn’t talk much about back then. Elmhirst was able to delve into the topic after finding letters that Maurice wrote later in life, after Maralyn died.

“He’s looking back over 30 or 40 years, and he’s grieving her, so there’s a layer of emotion that wasn’t there in the original book,” says Elmhirst, who also tracked down a friend who did the Baileys’ second voyage with them, to Patagonia, and knew them well.

The couple had only about an hour, Elmhirst says, to get themselves and whatever they could manage off Auralyn before it sank. Maurice was an experienced sailor, and he taught Maralyn, who couldn’t even swim. He navigated with a compass and sextant, and he insisted on heading offshore without any form of radio transmitter.

“He was sort of a purist,” Elmhirst says. “That was very much his way, his style of being in the world. He wanted to be cut off and isolated and to be really alone out on the ocean.”

Maurice had, she says, taken the preparations seriously for offshore cruising, which is why he psychologically collapsed after the boat went down. It was Maralyn, the author says, who had to figure out practical ways to catch fish and collect water, along with managing Maurice’s mental breakdown.

“He would always say that if it had not been for her, they never would have survived,”

Elmhirst says. “He was thinking about how they could kill themselves—was there enough gas in the canister to end it right now. Her optimism felt almost delusional to him.”

Being on that life raft, Elmhirst says, didn’t so much change the couple, but it did highlight who they really were.

“He took her out to the sea, and she opened up the world to him socially,” Elmhirst says. “I think that played out on the ocean and ever after, with her having to hold him together and make sure they survived.”

The impulse to head offshore in the first place, Elmhirst says, stemmed from Maurice’s upbringing and general dissatisfaction with life. To him, the ocean represented freedom, and the land represented restriction.

“I think it’s like that with a lot of sailors,” she says, “that time on land almost feels like time misspent.”

The months that the couple endured in the life raft ended up being far more than they ever bargained for, she adds. “You can make that choice, which seems like a choice of freedom, but you are then caught in a very intense situation on board. It’s not the freedom that you imagined. It becomes its own kind of restriction if your boat sinks and you’re trapped on a raft.”

And while it was Maralyn who seemed stronger throughout the ordeal on the life raft, Elmhirst says, it was Maurice who helped her blossom into the person she truly was.

“It was obviously still a marriage. I think there was a role that he played, to enable her to have that kind of strength and leadership,” Elmhirst says. “Maurice was willing to concede in ways that some men who are used to being in charge and being the captain maybe wouldn’t be.”

Overall, Elmhirst says, their core desire—to leave the world behind—is something that not only has become more prevalent throughout society since the pandemic, but that also affects just about everyone. That universal feeling is part of what she hopes A Marriage at Sea taps into for readers in the cruising community and beyond.

“It’s a fundamental human urge. It manifests in different ways. In some people it’s the mountains, in other people it’s the sea,” she says. “It’s the urge to escape that daily existence.”

July 2025