A small boat, a cold front and four anglers too far offshore —

A combination that quickly led to a worst-case scenario

The offshore fishing trip in the Gulf of Mexico that claimed the lives of three football players earlier this year reinforces the importance of tracking the weather, carrying proper safety gear and communications equipment, and recognizing the capabilities of your vessel.

“Football is a violent sport, but it pales in comparison to what these men were dealing with,” says Tom Rau, a retired Coast Guard senior chief and an authority on boating mishaps. “They were way out of their league. Those guys were big and strong, but it’s situational awareness that counts — and education.”

Two National Football League players — Marquis Cooper, 26, and Corey Smith, 29 — along with former University of Southern Florida player William Bleakley, 25, died after Cooper’s 2005 21-foot Everglades center console capsized in rough seas about 62 nautical miles off Clearwater, Fla. Nick Schuyler, 24, of Tampa, Fla., survived by staying on top of the overturned hull for 46 hours, clutching the lower unit of the boat’s single Yamaha 2-stroke. The others hadn’t been found as of press time.

The foursome was anchored and fishing for amberjack at 5:30 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 28, when the incident took place, according to a Coast Guard report that summarizes the survivor’s account of the accident. The anchor was stuck and, when the crew tried to raise it, the boat swamped and capsized. It’s unclear how they tried to free the anchor — or how many members may have gone forward to try and raise it.

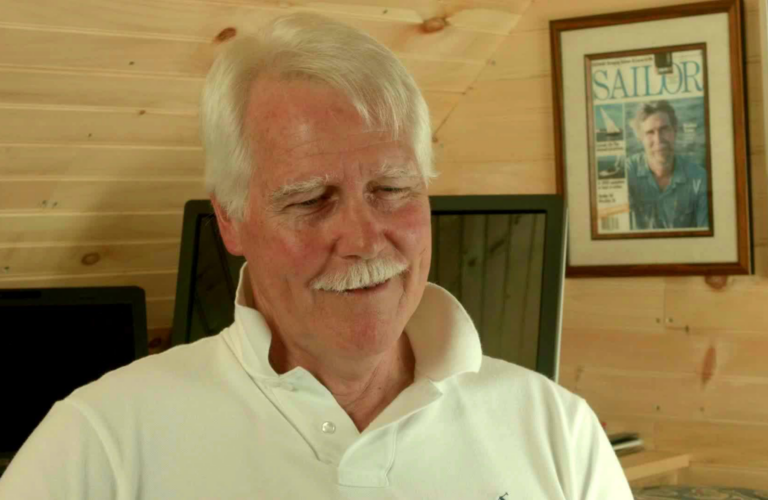

“Heavy weather calls for a scope of 10-to-1 or greater,” says Rau, who has published a boating safety book, “Boat Smart Chronicles.” The bow of the Everglades may have been pulled down while one or more of the men worked to raise the anchor, allowing water to pour into the boat, says Rau.

After the boat went over, Schuyler told investigators that everyone “grabbed the PFDs and were holding on to the boat for approximately four hours.” After that, according to Schuyler’s account, one of the victims “freaked out, took off his PFD, and disappeared during Saturday night.” Later Saturday night, a second man started “getting unruly, throwing punches.” Schuyler said that man also took off his PFD, dove under water and was never seen again. The third man thought he saw land either Saturday night or Sunday morning and decided to swim for it, Schuyler told the Coast Guard. That victim also reportedly said his PFD was “too tight and took it off,” according to the survivor. (The names of the four are blacked-out in the Coast Guard report.)

Schuyler was still wearing his PFD when the Coast Guard found him on the overturned Everglades 35 nautical miles west of St. Petersburg at about 3 p.m. March 2. It’s possible that the cold water and hypothermia played a role in the reported erratic behavior of the victims.

“We can all take home a lesson from this,” says Dr. Michael Jacobs, a sailor who teaches marine medicine and runs the Web site MedicineForMariners.com. “The survivor did the right thing by getting the majority of his thorax and his neck and head out of the water. The body cools 25 times faster when immersed in water.”

Cooper’s Everglades 211cc has a cutout transom, but the cockpit includes a raised area forward of the engine well to keep water out of the boat. It has an LOA of 20 feet, 9 inches, a beam of 8 feet, 2 inches, a 10-person capacity and a maximum load of 1,450 pounds, according to the builder specifications. Cockpit depth is 25 inches. The vessel has a 30-gallon live well and a 66-gallon fuel tank, and there were several portable fuel tanks on board Cooper’s 211cc. The boat had no kicker engine.

Like a snow plow

The anglers launched the Everglades — touted as a vee-hull bay boat with rough-water capabilities — at about 6:30 a.m. Saturday, Feb. 28, from the Seminole Boat Ramp in Clearwater. Cooper and his friends were headed to a wreck 62 nautical miles off Clearwater in a single-engine open boat at the same time a strong cold front was approaching.

At 9:42 Friday night, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration had begun broadcasting a small-craft advisory for Saturday night through Monday. NOAA predicted 15-knot winds out of the south and seas building to 3 to 5 feet for Saturday. Wind direction would shift from the southwest to west and increase to 20 knots Saturday night, with seas of 4 to 6 feet, followed by 20- to 25-knot northwest winds and seas of 9 to 12 feet on Sunday, according to NOAA.

Rebekah Cooper says her husband was aware of Sunday’s weather forecast and for that reason picked Saturday for the trip, according to press reports. But even with a small-craft advisory in place for Saturday night, wind and waves can build in strength and height in the immediate hours before a cold front arrives, according to Brian LaMarre, the meteorologist in charge of the National Weather Service in Tampa Bay.

NOAA’s forecast proved accurate, says LaMarre. Winds increased out of the south Saturday afternoon and early evening, and, as the front approached, winds shifted and seas began to build.

At 6:50 a.m. Sunday, a NOAA weather buoy recorded winds of 35 mph, with 40-mph gusts and 10-foot seas. Four hours later, seas had increased to 15 feet. The buoy is 100 nautical miles off the Tampa Bay area, so seas may have been smaller where the anglers were, says LaMarre.

Cooper had told another fishing buddy, inshore charter captain Clay Eavenson, that he “watched the weather” when he took his Everglades offshore. “The reports were that it wasn’t going to kick up till late [Saturday],” Eavenson, 31, told Soundings in an interview. Just three days before the fatal outing, Eavenson and Cooper had fished together on inshore waters. In fact, Cooper had invited him on the ill-fated trip, but Eavenson declined because he had a charter scheduled.

“At this time of year, it’s pretty normal to have these cold fronts come through,” says LaMarre. “The eastern Gulf of Mexico becomes very turbulent. We try to emphasize the cold fronts in our forecasts. They’re almost like a snow plow, slicing the warm air and pushing it upward and outward, creating increasing wind and seas.”

LaMarre points out that Tampa Bay area boaters can take advantage of NOAA radio weather broadcasts that can be picked up out to 60 nautical miles. The transmissions can be received on the 162.450 MHz VHF frequency.

No EPIRB

Eavenson is primarily an inshore fisherman and has ventured offshore just five times, but he knows the critical role an EPIRB can play in an emergency. “I asked [Cooper] if he had an EPIRB, and he didn’t know what it was,” says Eavenson. “I told him if I was going to run offshore I would have one. He said, ‘Yeah, I’m going to get one. If you say I should have one, I’ll get one.’ ”

Cooper had yet to purchase the emergency beacon.

Capt. Kip Louttit is deputy commander of the Coast Guard’s Maintenance and Logistics Command and an avid sailor who teaches boating safety courses. He points out that the Coast Guard can now home in on an EPIRB signal from its aircraft, using a DF-430 multimission direction finder, which is part of the agency’s Rescue 21 initiative.

“If I had to pick between a VHF radio and an EPIRB, I would pick the EPIRB,” says Louttit. “And I would have the right PFD. If you can float, and we have your position, we can find you and get you.”

In photos provided by the Coast Guard, Schuyler, the survivor, appears to be wearing a Type II inshore PFD. Another PFD recovered by the Coast Guard also appeared to be a Type II in the photos. Schuyler and his crewmates were not wearing life jackets when the Everglades flipped, according to reports, but Bleakley swam under the boat to retrieve PFDs for his crewmates.

The Coast Guard describes Type II PFDs as being suitable “for general boating activities.” They are “good for calm, inland waters, or where there is a good chance for fast rescue.” Because of their design and level of buoyancy, Type II PFDs are less likely to turn an unconscious wearer face-up than an offshore PFD, classified as Type I.

“Wear your life jacket, but you have to wear the right kind, especially when you’re 38 miles at sea,” says Phil Cappel, chief of the Coast Guard’s Recreational Boating Product Assurance Branch.

The Everglades, unsinkable with its high-density closed-cell urethane construction, gave the crew a fighting chance in the water, which dropped from 65 degrees Saturday, LaMarre says, to about 62 degrees Saturday night. The average person wearing light clothing and no PFD can survive in water of this temperature for approximately five to seven hours before dying from hypothermia, says Jacobs.

Survival time in cold water varies greatly, and how quickly hypothermia sets in depends on many factors. They include water temperature, sea state, body size and shape (larger people cool slower), the amount of body fat and clothing (internal and external insulation), how much of the body is immersed, state of health and fitness, and the amount of physical activity while in the water. “Get out of the water no matter how cold the air and wind chill,” advises Jacobs. “Get on top of a capsized boat if you can. Being in 40-degree air is better than being in 60-degree water.”

In addition to hypothermia, boaters need to be aware of another potentially deadly threat in cold shock response, a series of reflexes after sudden immersion in cold water that can lead to hyperventilation and subsequent inhalation of seawater, says Jacobs. “The initial phase of the cold-shock response is brief [two to three minutes], and your actions during this time can vastly improve your chance for survival,” he says. “It is imperative you try to bring your breathing under control while keeping your head above the water.”

The Coast Guard should be commended for carrying on the search-and-rescue mission for nearly three days, well beyond the time frame of survival, says Jacobs. The Coast Guard began searching at 2 a.m. Sunday, March 1, and called off the search Tuesday, March 4 at sundown. The agency used a hand-held GPS owned by one of the men to form search patterns. The GPS contained a waypoint “where they normally go to fish,” 50 nautical miles west of Clearwater, according to the Coast Guard report.

No formal float plan

Cooper apparently did not leave a float plan with anyone before getting under way. His wife began to worry when her husband hadn’t called later Saturday, according to published reports.

A proper float plan includes the boat’s registration numbers, size and model, along with at least two emergency phone numbers, the time the vessel is expected to return, the vessel’s communications and navigation equipment, safety and survival gear, the names of the crew and, of course, any intended destinations and typical routes. The float plan should be left with a person capable of contacting the Coast Guard or other search-and-rescue organization. The Coast Guard Auxiliary posts a float plan template on the Web site www.floatplancentral.org.

Cooper did have boating experience, according to Eavenson. “He said he had been going out on boats as long as he could remember,” says Eavenson, who runs a 22-foot Ranger bay boat from which he and Cooper caught redfish Feb. 26. “He’d been fishing his whole life. He was not an amateur.”

The others on board that day did not own boats, says Eavenson.

The four anglers may have been too complacent to the realities of taking a boat offshore, lured by benign conditions that can change quickly, says Rau.

“They probably set out in fine conditions,” he says. “The sky was blue, the water calm. They said, ‘Come on, let’s go.’

“The hardest thing is selling boating safety,” he says. “It’s one thing to be a boater, but it’s another to be a boater who knows what to do in an emergency.”

About a week after the accident, photos of the recovered boat became available. Dock lines were hanging from the rocket-launcher-style rod holders on the T-top. The crew could have used those lines — or the anchor rode — to help them stay with the boat or on top of the overturned hull, says Rau. The crew could have secured a line athwartships, from gunwale to gunwale, tying off to the low-profile bow rail, or stern or spring-line cleats. But it’s unclear whether those lines were accessible or tangled in the hardtop. Or whether any of the men had a knife or multitool to cut the lines free so they could be used to help secure themselves to the boat.

The safety gear boaters carry should be suited for the area they will be navigating. The shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico take many anglers far offshore to find fish. Therefore, emergency equipment such as an EPIRB, PLB, proper PFDs and a life raft are critically important.

Walter Szeezil runs a Contender 27 center console offshore for kingfish, amberjack, dolphin and snapper. In a ditch bag, he carries an ACR EPIRB with built-in GPS and a waterproof hand-held VHF. He also has a six-person life raft. On a night before a fishing trip, you’ll find Szeezil at his computer, checking the latest NOAA marine forecast on the Web.

“Sixty-two miles is a long way out, especially for such a small boat,” says Szeezil. “And March is a rough-weather month.”

The accident sent boaters in the Tampa Bay area in droves to chandleries and marine retailers to purchase EPIRBs. Wayne Seel, the manager of a West Marine in Sarasota, says customers were coming in talking about the accident. “We’re sold out of [EPIRBs],” says Seel. “It certainly has raised awareness.”

Not all boaters are aware of what an EPIRB is, even some who have been boating for years, says Eavenson. “Most boaters are weekend warriors,” he says. “These guys aren’t going to West Marine safety seminars or involved in the online fishing community.”

See the related article: “Surviving in cold water.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2009 issue.