We’ve all thought about it: buying an old fiberglass boat and fixing her up with a little cash and an ample application of sweat equity. It’s a way, at least in theory, to own a nice boat without spending a ton of money. But talk can be cheap—as cheap as a boneyard boat with grass growing in the bilges. Does the do-it-yourself concept play well in real life?

Ask Mike Zani of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, who is now sailing and racing a true classic plastic on Narragansett Bay. Vela is a reborn 53-year-old Graves Constellation that’s been brought into the 21st century.

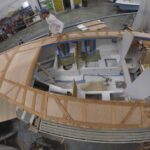

Rebuilding deck beams, carlins and house

Painting bulkheads and interior

Patterning for the deck

Installing decks on bulkheads

Vela is Zani’s second rebuild. His first was a 1962 Cape Cod Marlin, a fiberglass version of Nathanael Herreshoff’s 23-foot Fish, designed in 1916. The Marlin is famous for her graceful sheer, easily driven full-keel hull and not-so-pretty cabin trunk. Designer Ezra Smith, one of Zani’s racing crew, drew a new one—lower and less turret-like—that Zani built in plywood. Fresh paint and many coats of varnish later, the Marlin looked great. Zani, CEO of a software company, did most of the work himself.

Restoring a classic plastic boat is “really satisfying,” Smith says. “People think of old boats as slow, but back in the day, full-keeled boats were race boats, designed to sail as efficiently as possible.”

These old boats were solidly built and can be brought back to life with modern rigs and gear—but there’s a significant difference between restoring a 23-footer and a 30-foot boat like Vela.

“Before starting a restoration like this, it’s important to scope it out and decide if you’re going to be the general contractor or DIY it,” Zani says. That’s why he beer-can-raced Vela for a season. He discovered that she needed substantial work to make her just right. This would be no DIY job.

To get it done the right way, Zani enlisted Smith as well as yacht designer Matt Smith (no relation to Ezra) and Dan Shea, a boatbuilder who specializes in resurrecting classics.There are a “goodly number” of classic composite boats like Vela, Shea says, “handlaid of solid fiberglass by guys who gave a damn.” Restoring one is a good value-for-money project that usually can be accomplished with straightforward woodwork.

“Rebuilding the deck and structure is pretty much Boatwork 101,” he says. At least it is for a guy like Shea, whose Bristol Boat Company is next door to the Herreshoff Marine Museum in Bristol, Rhode Island, on the former site of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company.

Like many classic plastics, Vela has Herreshoff genes in her hull. The Graves Constellation is a 29-foot, 5-inch sloop, a typical cruiser/racer of the mid-1960s, designed by E. Selman “Jim” Graves of Marblehead, Massachusetts. Scuttlebutt says L. Francis Herreshoff helped draw her hull lines. (Herreshoff lived in a Gothic-style castle overlooking Marblehead Harbor, not far from the Graves Yacht Yard.) True or not, Constellations have a definite “Herreshoff-ness” about them, and are smart sailers, in that family’s tradition.

Graves built 27 Constellations between 1964 and 1971. (As for Vela, she launched in ‘65.) Each was essentially a wooden boat built on a fiberglass hull—the deck, cabin house, cockpit and interior were standard wood construction. Auxiliary power was an outboard in a well. As was common in the early days of fiberglass construction, the solid layup was heavy; builders 50 years ago achieved the required stiffness with thicker fiberglass and molded stringers, not balsa or foam coring. This construction kept Vela’s hull strong and stiff into her sixth decade.

But the boat’s wooden parts were showing their age: The cabin house and the deck had serious leaks. So, Shea applied the chop saw and started the rebuild with a bare fiberglass hull. According to Ezra Smith, her decks were originally built of Masonite, which “lasted pretty well,” but her hull-to-deck and deck-to-house joints were leaking. “She was going bad from the edges in,” he said.

Shea replaced the deck with two layers of marine plywood, bolted and epoxied to an inner flange that, he said, kept the hull stiff. He covered the plywood with fiberglass in epoxy, carrying the fabric over the deck edge and onto the hull for an even more secure joint.

Besides the wood, almost all the materials for Vela’s refit came from TotalBoat, a brand of boatbuilding supplies from Jamestown Distributors, also in Bristol. Zani is friends with Mike Mills, president of Jamestown, and sits on the company’s board of directors.

“TotalBoat was born in an effort to improve the products that we have come to trust and rely on,” Mills says. “Our own experience using and selling allowed us to develop products that we feel work better and cost less.”

Zani hoped to use TotalBoat products exclusively in the Vela project. And he did, almost: Only Awlgrip had the topsides color he wanted, and only Pettit had the bright white antifouling. Otherwise, everything else was TotalBoat, including some items not yet on the market. The project was done in TotalBoat’s shop, too. Vela was too big to fit in Shea’s place.

The boat races with four crew, but her original cockpit fit only three, so one goal of the rebuild was to add room for another backside, so all could sail “legs in.”

Ezra Smith redesigned the cockpit to fit everyone, but this meant lopping 2 feet off the after end of the cabin trunk. Zani also wanted to move the forward hatch from the cabin top onto the deck, a preference that required taking another few inches away. Shortening the trunk made it look boxy, so Ezra Smith lowered its profile, adding rectangular, Herreshoff-style windows to the varnished-mahogany cabin sides. The windows were a last-minute detail that gave the boat a true-classic look. (Nathanael Herreshoff used this style of window in his New York 30s, designed in 1905.)

As designed, Vela had rudimentary accommodations for four: settee berths in the main cabin, a head and V-berth forward of the main bulkhead, and a galley under the companionway. The bulkhead also supported the deck-stepped mast. Shortening the trunk made the already tight cabin even tighter, especially with the bulkhead bisecting the space. The solution? Remove the main bulkhead and support the mast step with a carbon-fiber deck beam. Zani asked Matt Smith to engineer the beam.

Zani also wanted to move the chainplates 9 inches inboard to reduce sheeting angles. Narrowing the spread of the shrouds increases compression load on the mast, so Smith had to recalculate for the new rig to spec the beam and determine how to tie it into the boat’s structure. Shea laminated the new cabin-top beams of solid carbon fiber, with plywood knees at each end to fit under Vela’s deck and tie into a new partial main bulkhead. (All of the boat’s new deck beams were laminated.)

The result was essentially a ring frame transferring the compression loads to the boat’s hull. Shea also built plywood knees to take the repositioned chainplates for the fore and aft lower shrouds. All structure was glassed into place with multiple layers of fabric and epoxy resin. The added rigging loads also required a new, larger section mast, which, serendipitously, turned out to be the same section used in the 30-foot Pearson Flyer. Zani found a used Flyer mast and modified it to fit Vela. He also added roller-furling gear, and had North Sails build him a set of 3Di Nordac seamless polyester sails, with a loose-footed mainsail that’s easier to bend on and permits cooler rigging along the boom, because there’s no track.

The rigging and deck hardware is all new, laid out by Zani, who also did Vela’s bottom.

Removing the bulkhead and adding the windows made the cabin more enjoyable, with better light and more room, even though it’s smaller overall, Zani says. The V-berth is a little bigger, and making it easier for sailors to move fore and aft. The smaller cabin still sleeps four, but there’s no room for the galley, which was already gone when Zani bought the boat. And he has no need of it. When he cruises with his family, they eat out of a cooler.

The racing crew can now launch and retrieve the spinnaker through the new round hatch in the foredeck, using a string drop; Zani added a roller abaft the hatch to make the process easier, and nobody has to leave the cockpit. “All this was from opening up the cabin,” he says.

The lower sheeting angle for the headsail lets the boat point higher, which resulted in a small regulations penalty for racing, but Vela can still sail faster than her rating, according to Zani. The new cockpit is more comfortable, even with all four crew on the seats; the new coamings are lower and don’t dig into the backs of the crew’s legs when they’re sitting on the side decks.

Zani says that despite this successful restoration project, he’s not likely to do another with a classic plastic boat: “No, not unless I felt there was a boat better than Vela.”

She’s good for two people to sail for fun, four guys to race, for sailing with the kids, and so forth. She’s faster and better-looking, and now has a better cockpit. The outboard in the well is efficient and stows in a cockpit locker when not needed. It all works great, Zani says.

But, he added, “There’s a chance I might start again with the same boat, but make a mold of the deck, rather than build it in wood, so other people could do it, too.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2019 issue.