Well, I’ve gone and done something silly. I’ve bought a 47-foot yacht called Tally Ho. She cost me about $1.30. She’s a 107-year-old Albert Strange design, a gaff-rigged cutter. And she needs a total rebuild.

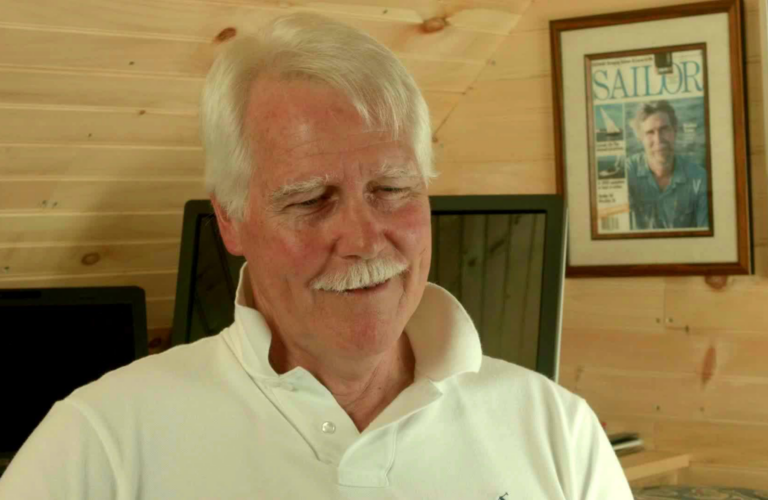

I left a good job on a beautiful superyacht to live with Tally Ho in sawdust and squalor in stunningly beautiful but very remote Sequim, Washington. On a personal level, it’s the calling of independence and challenge. It’s about risking everything for something stupid and beautiful. And most of all, it’s about doing something that will make a good story — because for me, that is important in life: to have good stories to tell and to have good people to tell them to.

On a higher level, rebuilding Tally Ho is about saving a piece of history that is in danger of being lost. Strange, who lived from 1855 until 1917, was an esteemed designer, beloved for his elegant canoe-stern yawls and his advancement of yacht design through literature. He exhibited many times at the Royal Academy of Arts, and his broad spectrum of passions and skills endears yachting enthusiasts to him. Tally Ho is one of Strange’s largest designs and certainly the largest in existence today.

She gained fame for winning the third Fastnet race, in 1927, beating such proven vessels as Jolie Brise and Ilex. Later, she proved a seakindly world-cruising yacht, although she was nearly lost to a Pacific reef and subsequently disappeared. She was rediscovered years later in a tiny port in Oregon, where she had been used to fish for salmon before being left to rot on the dock. There have been various attempts to save her, but her obscure location and state of disrepair have made doing so difficult.

When I went to look at her, I was astounded by the amount of work to do, but I was also surprised that the planks were mostly in good condition, and the huge keel timber was solid teak.

Washington state was the nearest place with a traditional sailing community, and I was generously offered the use of land and a workshop — big enough to accommodate a few beds for volunteers and myself. The Albert Strange Association, which had sold me the yacht for just $1, contributed toward the cost of moving her there.

People offering help and support asked how the project made me feel, and I replied “excited and terrified” because I knew the scale of the work to be done. When I considered my answer further, I realized that I’d felt the same just before every silly decision I’d ever made. All of those decisions became the most important and worthwhile milestones in my life.

One of the times I experienced that same sensation was in 2012, when I spent my meager life savings on a 1947 Nordic Folkboat. I rebuilt her on a shoestring for 10 months and sailed her — Lorema, after my grandmother — across the Atlantic to the Caribbean. I chose to sail without an engine or GPS, and although it was challenging at times, it was the most rewarding journey I have ever taken. It made me think about the values we attach to experiences and risks, and the things we gain from them.

The Lorema trans-Atlantic led me to skipper the 1927 ketch Sincerity some 9,000 miles from Antigua to Italy — the long way, via summer charters in Greenland. Then I found myself as the bosun on the 213- foot, three-masted gaff schooner Adix, sailing up and down the Eastern Seaboard by cruising from Cuba to Maine and back again.

Being involved in the superyacht industry was interesting, and I have been witness to enormous wealth, but nothing comes close to the exhilaration and freedom of doing something for yourself, by your own means. The rebuild of Tally Ho is just such a challenge.

Although I have worked on and off as a boatbuilder for the past seven years, I have never undertaken a project as big as this one. The ballast keel and keel timber will (hopefully) be saved, but other parts of the centerline will have to be replaced. Most of the frames will have to be replaced, too, because the oak futtocks were side-fastened with steel and have suffered rot. The planks are fastened with copper rivets, which means many of the teak planks can be saved, although most of the fastenings will be replaced with the frames. The deck planks and most of the deck structure will have to be replaced, too, but some deck hatches and coamings might be salvageable. She has no spars or rig or interior or engine or systems, so they all have to be fitted from scratch, but that effort is a long way down the line, so I’m avoiding thinking about it too much for now.

Strange’s original sail plan (dotted lines) as drawn by Ian Oughtred

Tally Ho on a port tack.

Tally Ho running downwind with an enlarged racing rig.

I am starting this project with my savings from the past couple of years, but I may not have enough to do the whole boat in one go, so I will probably work periodically unless I find funding. I intend to work hard and fast, but I am determined not to compromise on quality of work or materials. Stow & Son in Shoreham, U.K., built Tally Ho to a high standard, and I intend to restore her to at least the same quality. If that means working an extra few months here and there to use bronze rather than steel, so be it.

I will try to stick to traditional methods and technology, too, although I may not go so far as installing a paraffin engine, for obvious reasons. I will need volunteers who will work for accommodations, experience and skill-building.

Tally Ho has already been moved by truck some 600 miles to Sequim. I spent a week building a shed over her. And I am making short films about the project to provide a historical record. The first two films are already on my website (sampsonboat.co.uk).

After Tally Ho is sailing again, I hope, she may become a platform for learning traditional navigation and sailing skills. This may be on a charter or charitable basis, or with family and friends. I am keen to cruise the Pacific and explore some remote corners of the world. The high latitudes appeal to me, so I will install a wood burner, as per Tally Ho’s original drawings. She will also race in classic yacht regattas and may even be able to sail in the 2027 centenary of the Fastnet race that she won in her heyday.

Many people will think of this as an optimistic project. It will take huge amounts of time, commitment and money, and I will need help. The work will be an adventure in itself, and will have its highs and its lows, but I am grateful for the chance to bring such a historic vessel back to life. I hope that whatever happens, it makes a great story.

This article originally appeared in the November 2017 issue.