IN THEIR WORDS

Boating can be a lifetime sport. You might have to give in a little to age along the way, but even that can have surprising — and gratifying — results.

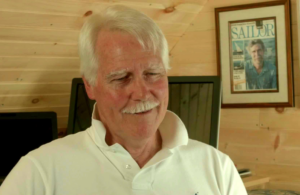

Take Hugh Smith, a photographer from Southport, Conn., and his wife, Sally. Smith, 70, a native of Mystic, Conn., has been around the water all his life. “I owned a boat before I owned a bike,” says the sailor. He has cruised and competed, sailing in the Newport-Bermuda and Annapolis-Newport races, and covering much of the East Coast with his family. But the time came when the Smiths’ Hinckley Sou’wester 42 became too much for the couple to sail by themselves. Yet they still wanted to stay in touch with the water. So the sailors bought a powerboat.

Today the Smiths do their cruising aboard a Hinckley Talaria 42, a single-screw Down East flybridge sedan from the drawing table of Maine lobster boat designer Spencer Lincoln. In fact, it was just the boat Smith wanted to replace his beloved Sou’wester. “I looked at the Talaria 42 and saw the same knobs, the same hinges and hatches, the same varnish work as the sailboat,” he says. “It was all there in the powerboat.”

Smith says the vintage 1991 42-footer was an easy buy in 2003 for about $350,000. “It was in excellent shape,” he says. “It had just two other owners, one who hardly used it and another who had a captain maintain it.”

Still, after 16 years of sailing, selling the Sou’wester wasn’t easy. “We would sometimes go out for weeks at a time — the Elizabeth Islands [off Cape Cod], up to Mount Desert [Maine], to New York,” recalls Smith. “It was a wonderful boat. After we sold it, I cried on the way home.”

The Talaria 42 has helped ease the pain. It’s comfortable, capable and self-sufficient, like the sailboat, says Smith. “It carries plenty of fuel and water, so you’re not always looking for a marina to tie up to,” he says. Handy gear includes a generator, watermaker, anchor windlass (no more hauling by hand), and removable davits for the inflatable.

She rides a semidisplacement hull powered by a single 425-hp diesel. “At 2,400 rpm, I’m doing about 12 knots and using about 12 gallons an hour,” says Smith. “She’ll do 15 knots, but I don’t usually push her that hard.” And the merits of a single engine have become evident. “There’s a big single screw with a big rudder back there, and she’s easy to maneuver. I did add a bow thruster, because [Southport] harbor is so small. The speed’s OK with me, and with a single engine there’s only one of everything, as far as maintenance goes.”

The layout suits the cruising couple, with its private master cabin and fully equipped head compartment with shower. In the Smiths’ boat, the galley is down but open to the main cabin above. The saloon, lit by large side windows, has a custom television stand incorporating a couple of single seats, and a built-in lounge across the way. There’s also a lower helm station, which Smith calls a “great asset” on his cruising boat. The station has a large nav/chart table, a practical touch Smith appreciates.

But it’s on deck where the layout works best. The cockpit is roomy, and the flybridge with the upper helm station is a popular hangout. “I spend a lot of time up there,” says Smith. “It’s open to the breeze, and you can see everything around you. It’s a nice place to be when you’ve dropped the hook for the day, too.”

A typical cruise in the Talaria might be a run across Long Island Sound to Port Jefferson, N.Y., where the couple may spend a weekend. But Smith single-hands the 42-footer a lot, too, and he’s at home on the local waters and with those who ply them. On an afternoon ride he points out the collier off Penfield Light, the research vessel towing bottom-mapping equipment, the local commercial oyster boats.

“I love to take this boat out myself sometimes,” says Smith, looking out from the flybridge helm. “I feel like I’m in my element, in a place I’ve been familiar with all my life.”

It’s called staying in touch with the water.

WALKTHROUGH

Hinckley’s Talaria 42 in the 1990s helped start a trend that has put the Southwest Harbor, Maine, boatbuilder on the powerboat map and the term “Down East” firmly into the mainstream. Maine designer Spencer Lincoln borrowed from the lobster boat in giving the Talaria a full-keel, semidisplacement (albeit chined) hull. The sharp entry flattens quickly, ending with just 5 degrees of transom deadrise. The keel and protected rudder further reflect workboat designs.

Basic construction used a Kevlar-fiberglass hybrid cloth with solid fiberglass at stress points and some balsa coring. Hinckley offered a pair of bilevel interior layouts for the Talaria 42. Both have a forward master stateroom below with an adjacent head to starboard, and the two-cabin layout puts a guest cabin to port, while the other has a galley-down to port. The two configurations each incorporate a lower helm station in the saloon — where there’s room for lounge and individual seating — and in the two-cabin layout a galley-up is to port, next to the helm. Interiors were finished in a variety of varnished woods, including teak and cherry.

On deck, the flybridge and upper helm station are reached by ladder from the spacious cockpit. Wide side decks and an open foredeck ringed by a bow rail make for safe transits around the boat. Power comes from a single diesel (a variety of models were offered) of around 425 hp to 500 hp.

AVAILABILITY

Because just 17 boats were built before the Talaria 44 replaced it, the Talaria 42 isn’t an easy find on the used-boat market. Most are situated along the East Coast, and prices begin in the low- to mid-$300,000 range. An “impeccable” flybridge model, vintage 1995, was for sale in Maryland for $399,000. The newly Awlgripped dark blue hull is topped by a varnished toe rail. The two-cabin, galley-up interior is trimmed in cherry, and there’s a teak-and-holly cabin sole to go along with such amenities as air conditioning and heat. Single-engine power comes from a 400-hp Cummins diesel (less than 1,000 hours) for a cruising speed of 12 to 14 knots. Recently added equipment includes a bow thruster, trim tabs, generator and radar, in addition to a new teak swim platform. The Hinckley Co. also maintains a brokerage listing of Hinckley and other yachts at www.thehinckleycompany.com .

BACKGROUND

The Hinckley Co. has been a leading name in boatbuilding since 1928. Henry Hinckley, armed with a degree from Cornell University, took over his father’s Maine shop in 1932 and established a reputation for quality construction in both sail and power. In 1955 Hinckley began experimenting with fiberglass, and five years later he turned out the first of some 200 fiberglass hulls for the Bermuda 40, a racing-cruising sailboat considered a classic today. That same year, the builder produced its last wooden powerboats. Other innovations through the years include the early use of Kevlar-fiberglass hybrids, resin infusion layup techniques, jetdrive propulsion and joystick-style controls.

Today, Hinckley builds powerboats from 29 to 55 feet and sailboats from 42 to 70 feet. An early entry in the Down East cruising boat market, the Talaria 42 debuted in 1990 as a 39-footer. The design was quickly altered to add room to the cockpit and renamed the Talaria 42. Seventeen boats were built before production was ceased after 1998.

SPECIFICATIONS

LOA: 41 feet, 9 inches

LWL: 38 feet, 7 inches

BEAM: 13 feet, 8 inches

DRAFT: 4 feet, 4 inches

DISPLACEMENT: 22,000 pounds

HULL TYPE: semidisplacement

PROPULSION: single diesel

TANKAGE: 400 gallons fuel, 110 gallons water

BUILDER: The Hinckley Co., Portsmouth, R.I.

Phone: (401) 683-7005.