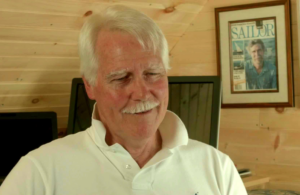

Offshore wind farms have run into stiff head winds in a Coast Guard study of the effect they could have on navigational safety in Atlantic waters from Maine to Florida. The wind farms “will confuse airborne radars and also will confuse seaborne radars and create a wall of clutter,” says sailor Benjamin C. Riggs of Newport, R.I.

A retired Navy captain, offshore racer and sailing instructor at the Navy War College and Naval Academy Preparatory School, Riggs was one of more than 30 people and organizations who answered a Dec. 9 Coast Guard request for information about how wind farms might affect existing shipping routes and waterway uses. The Coast Guard says it wants the information to help ensure that wind farms don’t jeopardize safe navigation.

In an interview, Riggs — a vocal critic of the 130-turbine Cape Wind project approved for Horseshoe Shoals on Nantucket Sound off Massachusetts — says mariners can’t see through or around the wall of clutter that marks a wind farm on the radar. This creates a navigational hazard — at night and in fog, especially — and prevents skippers from using radar to “pick their way through” the maze of turbines.

The Cape Wind turbines, rising 258 feet above the water, will be spaced six to nine football fields apart and cover 24 square miles. Sailors, even under the best conditions, wouldn’t want to try to tack through this forest of windmills, Riggs says.

Powerboaters, on the other hand, could motor through, and anglers especially might well want to because the structures draw fish, says Capt. Lindsay Fuller, a charter fishing captain from Beach Haven, N.J. Recreational anglers are drooling at the prospect of wind farms going in off New Jersey, he says. “There’s not a whole lot of rock around here like they have up in Maine,” says Fuller, president of the 14-boat Beach Haven Charter Fishing Association. “All we’ve got is sand. There’s not much accretion for anything to grow on.”

For about five years in the 1970s and early ’80s, oil companies drilled off New Jersey at the 60-fathom line, creating new and productive fishing grounds around the rigs for anglers bold enough to motor out. “We could go right up to the rig,” Fuller says. “Fishing was absolutely fantastic in those years. We hoped they would hit it big [and strike oil].” The drilling didn’t go well and the exploration teams packed up and left.

Fuller wrote to the Coast Guard that his association is fully in favor of the wind farms. He believes the turbines could be just as productive for anglers as the oil rigs, which long have been popular fishing spots in the Gulf of Mexico. “Our biggest concern is that they will claim some security issue and try to keep us away from the turbines,” Fuller says. “If they did that, we’d fight them tooth and nail.”

The Defense and Homeland Security departments have studied the interaction of radar and wind farms and, like sailor Riggs, they have serious concerns. A 2008 study for the Homeland Security department found that wind farms could create dead zones where air-defense radar can’t detect aircraft, weather radar software could misinterpret the high apparent shear between the turbines’ blade tips as a tornado, and air traffic control software could temporarily lose the track of aircraft flying over wind farms. The authors thought technical upgrades in the radars could mitigate these problems, but in the absence of surefire fixes, military commands have blocked wind farms from going in where they could interfere with radar operations.

Riggs agrees that conflict between wind farms and vessels in navigation, including interference with radar, probably can be mitigated, but he says there’s no reason to do that because wind power is much more costly than other alternatives (three to five times more expensive than natural gas), it barely reduces our dependence on foreign oil (only 1 percent of electricity is oil-generated), and wind power only makes economic sense if large federal subsidies underwrite it. “It’s not a solution,” he says.

Another sailor, Bruce Chappell, who cruises the East Coast with his wife, Judy, on their Pearson 38 and manages the east yard at Brewer Pilots Point Marina in Westbrook, Conn., takes the more moderate view that adjustments can be made to the locations of wind farms and to vessel routing so turbines and boats can coexist. Chappell says his main concern is for boaters cruising between Long Island Sound and popular destinations on Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. The navigation and seamanship skills of many who cruise those waters are “a little sketchy,” he says.

Will a wind farm go in along the most direct route to these destinations and, if so, will they have to divert long distances? Will they have to press closer to shore? Will they be able to tell the difference between the lights on the turbines and the night lights ashore? Will wind farms make their cruising more difficult and dangerous?

He says he also worries that if the Coast Guard recommends preferred vessel routing into and out of major ports along the East Coast to avoid wind farms, as it says it might, pleasure boaters could find themselves funneled into traffic schemes with more and commercial traffic — container ships, tugs and barges, and tankers. “We could see a lot more accidents,” he says.

Boaters could face a dilemma: “Go through the wind farm to avoid commercial traffic or go with the commercial traffic to avoid the wind farm,” he says.

Nonetheless, Chappell thinks wind farms probably are inevitable and necessary. “We need the power,” he says. “If we can find acceptable places to put them we should be able to move forward pretty quickly [on wind power],” he says. “We just have to make sure we pay attention to the cruising boater out there as best we can.”

Commercial shippers have been even more attuned than boaters to the Coast Guard study, which is still in its information-gathering stage. (The deadline for submitting observations for the Port Access Route Study: The Atlantic Coast From Maine to Florida, Federal Register citation USCG–2011–0351, was Jan. 31.) They are concerned that the rush to develop wind farms is outpacing efforts to protect navigation, says Christopher Koch, chief executive of the New York-based World Shipping Council.

“Our concerns were highlighted when [the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement] started proposing wind farms in shipping channels,” he says. “If you’re going to have a coherent plan for locating wind farms, the [Coast Guard] study helps do that in a more intelligible fashion than the first rollout.”

Besides permitting the Cape Wind project, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management has issued five interim leases for wind farm development off the Mid-Atlantic — four off New Jersey and one off Delaware. Offshore wind farm proposals or studies are under review in Maine, Florida, Maryland, New York, Virginia and South Carolina, according to the bureau.

Is offshore wind power in the cards for the East Coast? “I think it is, looking at all the proposals right now,” says Bill Broadley, a coastwise pilot based out of Chesapeake City, Md.

Broadley, who pilots vessels along the coast from Long Island Sound to Chesapeake Bay, has the ear of both commercial vessel operators and the Coast Guard. He is proposing voluntary traffic separation schemes for a number of East Coast ports that would alert regulators where not to put wind farms. The schemes consist of a mile-wide one-way lane going into the port, a mile-wide lane going out, a mile between the lanes and a half-mile buffer on both sides of them — a 6-mile-wide slot for marine traffic only, not wind turbines.

“You’d think with the great big ocean out there we’d have plenty of room to do what we want,” Broadley says. “But there’s a lot of stuff going on out there. I think we can work it out, but I’ve talked to other commercial [shippers] who say, ‘No, we can’t work it out.’ ”

They don’t think there’s room for wind farms and marine traffic close to the coast, where it’s most economical to locate the farms. The water is shallow, so it’s less costly to install the turbines, and the electrical transmission distances are shorter.

“I disagree,” Broadley says. “I think we can coexist.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2012 issue.