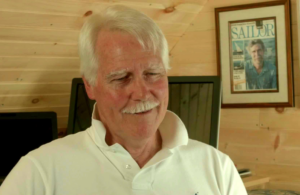

Fate made him surgeon to the Swan

Medical trainee traded his scalpel for a gelcoat peeler and started a high-end marine practice

“It was Michener,” says Matthias Muench, without hesitation, his German accent barely discernible. “During my cruising days, I read his book ‘Chesapeake,’ became intrigued, and decided to check this place out.”

That’s how he came to Annapolis, Md., 20-odd years ago. He liked what he saw — and the woman he met — so moving ashore wasn’t painful but a rather logical progression from a nomadic life on the ocean to a settled existence on the hard.

Muench, born and raised in Essen, a landlocked part of northwestern Germany, is known as Marty around the waterfront. How Matthias morphed into Marty instead of Matt he can’t say, but that’s just as well, because he made a name for himself in the boat restoration business — with a clientele that loves luxury. In the process of carving out his niche with the wealthy, Muench became a success himself while remaining grounded in his principles. His swagger might be interpreted as arrogance, but that misses the point, because the man worked hard to get to where he is and made some smart decisions along the way.

Detours and destiny

His story could easily have turned out differently had he continued on his original course of a career in medicine. But life forced him into some unexpected tacks, and everything changed.

As a German medical student in the 1980s, he was accepted at McGill University in Montreal but soon discovered he preferred the climate on Canada’s West Coast, so he moved to Victoria, B.C., to attend Victoria University. During those long summer days in the Pacific Northwest, he raced Lasers, 6- and 8-Meter yachts and learned the ropes of vessel maintenance while jobbing for a Danish guy, who built cold-molded vessels in the area.

At one point Muench thought he’d done enough dirty work for others, so he went home to Germany to attend medical school there. Shocked by the rigid system and bent on avoiding a predictable career path, he dropped out. Nearly broke but desperate for adventure, he traveled in 1985 to the U.K., where he shelled out his last shekels (nickels) to buy Golden Sovereign — a dated, no-frills 34-footer by Camper & Nicholson, sans engine or batteries — and sailed her from England via Madeira and the Canaries to the Caribbean and, lured on by James Michener’s book, to the Chesapeake.

Today, Muench does business mostly under the shingle of Osmotech, which hints at his origins in “osmosis correction,” aka blister repairs. The comfort level of such a procedure is akin to a root canal — messy, painful and often the only way to save damaged goods, i.e. waterlogged hulls of vintage fiberglass boats. The ingenuity behind it was the “gelcoat peeler” Muench developed in 1989. The power tool revolutionized blister repair, because it drastically reduced the time required to strip the fiberglass laminate so the affected area can dry out before being rebuilt.

Flirting with the Finns

For years, Muench and his partner at the time, John “Kiwi” Bell, had plenty of blister business, repairing boats for owners or manufacturers who had to handle warranty claims. It was lucrative, he says, but also monotonous — “like flipping burgers.” He looked for another challenge and started buying project boats he could fix up. From the get-go he specialized in commissioning, repairing and restoring Nautor’s Swans, which are as far up on the totem pole as production sailing yachts go. His first project was a run-down Swan 43 he fixed up for some cruising on the Eastern Seaboard and in the Caribbean with his American wife, Melanie. The couple still does that, but today their boat is bigger and they are joined by daughters Molly, 15, and Mia, 14.

Another reason he is partial to the “Rolls Royce of the Seas” (built in Finland near the Arctic Circle), is that he’s a stickler for details and loves the company of other sticklers. “Germans are square-heads, you know. We’re obsessed with engineering. But we can’t hold a candle to the Finns, who are even more square-headed and obsessed with engineering.”

Understanding the different periods of design and construction of these boats is a prerequisite, he says. “Swans have a unique DNA, and one must understand that.” He has a special affinity for those built between 1980 and 2000.

Now that Nautor’s Swan is owned by Italians, Muench thinks a clash of cultures could be looming because, he says, Italians love flashy and fast, while Finns love doing things for eternity. Making boats lighter and faster reduces their longevity, Muench explains. But that’s incongruent with Swan’s original philosophy, which embraced sturdy construction that helped boats retain high value and made them suitable for high-end refits even at an advanced age. “However, sailing no longer resembles camping on the water,” Muench says. “Today, there’s so much stuff that goes into boats, which makes them heavy, so even Swan builds lighter to achieve good performance. In a way it is like robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

‘A one-stop shop’

His ability to rehab floating (or half-sunken) wrecks that were written off by insurers creates value simply because nicer sells better. And Muench has the skill to turn these castoffs into objects of desire.

Last year, when the currency exchange rate favored exports across the pond, Muench restored three vintage Swan 44s that were destined for clients in Italy, Finland and the U.K. Whether it’s minor cosmetic repair or major reconstructive surgery, there’s hardly anything Muench can’t or won’t do.

“Swan owners want the best, so they ask for the best, and that typically brings up Marty and the quality of his workmanship,” says Keith Yeoman, of the Nautor’s Swan Newport, R.I., office. Yeoman has known Muench for years, and refers clients to him.

“He’s a one-stop shop, which is what owners want,” says Yeoman. “They don’t have time to deal with subcontractors. That’s up to [Muench].”

One such owner is Frank Mavronicolas, a commodities trader from Lloyd Harbor, N.Y., who had his vintage Swan 57, Boonatsa, brought up from Tortola for a little TLC at Osmotech. The job included a new engine and new floors. To Mavronicolas, such a commute is worth the trouble, because, “Marty’s an artist, and what he does is done right.”

Another booster is Peter Houghton, who owns and operates the Swan 68 Y2K, a boat he used to work on before he bought it. His job list included new paint, new wiring and a new teak deck, which is a Marty special, since he meticulously cuts the planks from Burmese teak and lays them by hand, without screws. That’s not cheap but high on the Gucci scale.

While Muench epitomizes German craftsmanship, it must be noted he also has a knack for bluntness. “He’ll speak his mind, and that might rub some people the wrong way,” says Yeoman. “His German-anal attitude toward workmanship and the results he produces are utterly convincing — but an owner has to get through the first 30 minutes with him.”

No desire to grow

Muench’s shop in the Maritime Republic of Eastport, near the end of Second Street, next door to J-World on Back Creek, is small and low key, which is part of a business strategy that avoids willy-nilly growth. While this might have seemed foolish in the fat years, it’s a blessing in times like these, where cost control is half the rent.

Entering from Second Street, there’s a tiny front office that is managed by “Barb” Paulin, who’s been with Muench from the start. The small workshop behind the office is crammed with tools and lumber, while the boats are jacked up on the gravel lot or end-tied to one of the docks in the small marina.

“I’m not interested in getting bigger,” Muench says. “I have very little overhead. I know what I can handle and that’s where I am today. Anything beyond that is too much, because it would require more management, more infrastructure and more capital.” Besides, he says, it’s tough to find qualified labor because there are not enough apprenticeships for aspiring boatbuilders in the U.S. He employs no more than seven people at one time, drawing from a pool of 20 workers. They’re Brits, Swedes, Kiwis, Aussies and Latinos who understand the business and work to his standards. But most of them are sailors, too, so he has to shuffle the lineup.

Island house calls

Even in this rocky economy, Muench says, he has more work than he can handle — more than in previous years. That’s why he hasn’t launched his business Web site. “People might not buy new, but they still maintain and restore their old boats,” he says. If necessary, he will skip town to help customers, e.g. if a boat’s stuck in the Caribbean and the problem can’t be fixed on location.

“If this happens, I take the next flight out,” he says. “I order spares to be drop-shipped to the boat’s location, then I download the manuals from the manufacturer’s Web site to study them on the plane, so I’m ready for action when I get there.”

In the winter, he spends time with his family at his house in Puerto Rico, where he keeps his vintage Swan 57, Concerto, which is maintained in Bristol condition, to cruise, relax and entertain, or to rendezvous with clients.

“Compared to working as a doctor in some hospital in Germany, it’s a very nice lifestyle,” Muench says.

He ditched a career as OB/GYN or surgeon to work in boat health care, wielding sander and plane instead of scalpel and forceps. His clinic is in Annapolis, but he also conducts occasional “house visits” in the Caribbean. Those unforeseen tacks years ago put Muench on a fine course in life. Michener surely would have approved.

Dieter Loibner is sailing editor for Soundings.

This story originally appeared in the February 2009 issue.