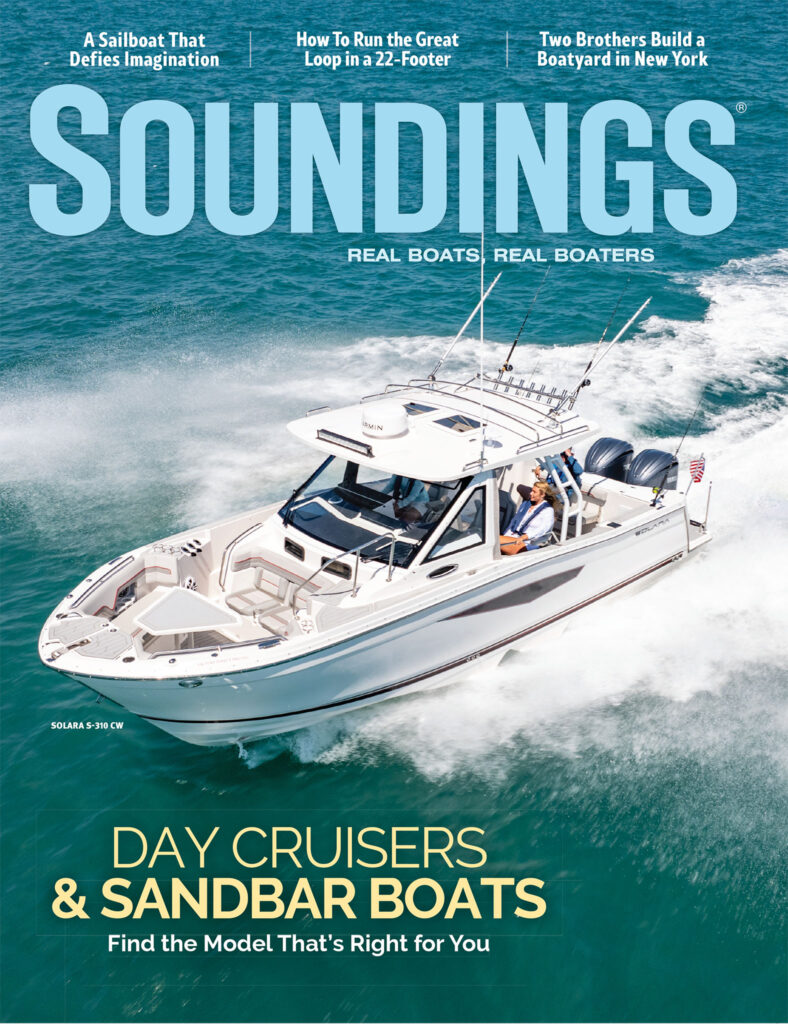

I’ve beached a few boats in my time, some of them even on purpose (kidding). Beaching is typically the easy part; avoiding damage and unbeaching when it’s time to head back to the dock is another matter. There’s an art to it, whether you’re on an outboard-powered ski boat, a RIB tender or a PWC with a jet drive.

When approaching the beach, power slowly forward while perpendicular to the shoreline. Coast in, bumping the engine in and out of gear if the shoreline is steep and you have room. Then put it in neutral, turn the engine off and tilt up the outdrive to minimize draft.

When coming in, watch your depth finder and/or eyeball the bottom. Traditional wisdom says you should be in waist-deep water before someone jumps in to hold the boat until you’re ready to pull it up on the beach. However, I’ve gone in a few times up to my neck because it can be hard to judge the depth without a sounder. I’ve used a paddle to test the depth but that’s better in theory than in practice, especially if there’s current.

Ideally, you’ve identified a sandy spot in advance, but shells, coral, rocks and branches are easy to miss from a distance. Try to avoid this natural debris if possible, as it can damage thru-hulls, depth sounders and gelcoat—and in the process, allow water into the fiberglass laminate. Rocks and shells can also scrub off antifouling paint and hurt bare feet, so bring water shoes.

The next step is to unload your crew and gear. That will make the boat lighter, so you can get it farther up the beach. Then, attach a line to your boat’s bow and walk it about 30-plus feet up the beach, or farther if possible. Legally, you can’t tie off to living things like shrubs and trees. You can tie up to a stake you pound into the sand; or you can attach the line to a grapnel anchor and push the flukes deep into the sand. Tighten up the bow line and set a lifejacket over the anchor so it’s visible and doesn’t become a tripping hazard.

Unless you adjust the location of the boat every hour or two with the tides, you may be left high and dry on a falling tide, or your boat may leave without you on a rising one. Also, even in a calm cove, you may get waves splashing into the outboard well of a boat that’s bow to the beach. These waves can be wind generated or created by other craft zooming by. They can turn your boat sideways too, pummeling it and making it harder to relaunch. If you want to relax on a sandy island for a long period, then don’t beach the boat. Rather, anchor with the bow out, which will come in handy if a storm arrives and you need to leave quickly.

If you beach your boat often, a keel guard could be a worthy investment. This strip of abrasion-resistant polymer can be glued onto the keel and protects your gelcoat from hazards. A bailer is handy too, if water splashes into your dinghy or the motor well. And because it can sometimes be challenging to unbeach, or relaunch a boat on your own, bring a friend along to help.

I learned that lesson the hard way on a two-day PWC outing down the ICW with a group. We stopped for a beach barbeque and pulled our Sea-Doo Pro Explorers just barely onto the beach, where we staked them. Over the course of our lunch, these 600-pound machines dug themselves into the sand and created suction. That made it a bear to get them back into open water, where we could start the jet drives. Sand and debris, we learned, can also work its way into the jet pump or driveline. It would have been smarter for us to anchor the craft off the shoreline to avoid damaging the cooling system.

This suction happens to all kinds of boats, especially on sand or mud. However, if you’re running a boat with a propeller and water intake that are still in clear water you can put the engine in reverse and swing the partially lifted motor back and forth, creating a sort of fan effect under the boat. This sculling motion can sweep water under the boat and help pop it loose.

You can also, use crew weight to your advantage when re-launching. Simply move your passengers aft. Too many times, I’ve watched bow riders try to leave with the crew all snuggled up forward and the bow well stuck in the sand.

Two other ways to enjoy the sandbar are anchoring and rafting up. To anchor bow out in shallow water, where the hull never touches the sand, you’ll need two anchors. First, move the bow anchor and rode to the stern on one side of the boat as you’re slowly motoring in. Lower the anchor slowly, keeping it clear of the prop, and set it. Power forward to your desired final location. Then, take the stern anchor on the opposite side of the boat, walk it up the beach and plant it. The boat will pivot to a bow-out position. The engine should be trimmed up and off at this time. A grapnel anchor will work well on the beach and your regular claw or Danforth anchor with a bit of chain is good in the water. Once you unloaded snug up the lines so the boat sits steady between the two.

To enjoy a day at the sandbar, you can also raft up with other boats. After one or two boats are anchored bow out in shallow water, others may tie on. The largest boats in the group should have an anchor down. Tie up with plenty of fenders and small bits of line. The boats will move differently in waves, so keep hands, fingers, and feet clear of the fenders and tie lines. This is the least flexible way to stay near the beach and it takes a while to un-raft so if you see weather coming, start the process immediately.

Most outboard-powered boats are beachable, especially if the motors can be lifted easily. Pontoon boats are straightforward with the bows beached while the prop stays in deeper water. Sterndrives can be trimmed up as well. Jet drives are tricky, and inboard boats should never be beached or you’ll damage more than just the gelcoat. In a pinch, the owner of an inboard boat can beach a small RIB tender; if it gets stuck, you may be able to horse the bow around rather than pull the heavy stern against the sand.

Ultimately, the key to beaching is communication with your crew. Assign tasks ahead of time and confirm that everyone understands their responsibilities before approaching the shore.

Another take: you can do it, but should you? It depends on the type of boat, your gear, the location, the bottom composition, the conditions, the crew, and the confidence you have in your skills. If in doubt, anchor out. Practice doesn’t make perfect, but it helps so try it a few times under ideal circumstances and then go enjoy the sandbar lifestyle.

This article was originally published in the June 2024 issue.